15 November 2020 | By DF

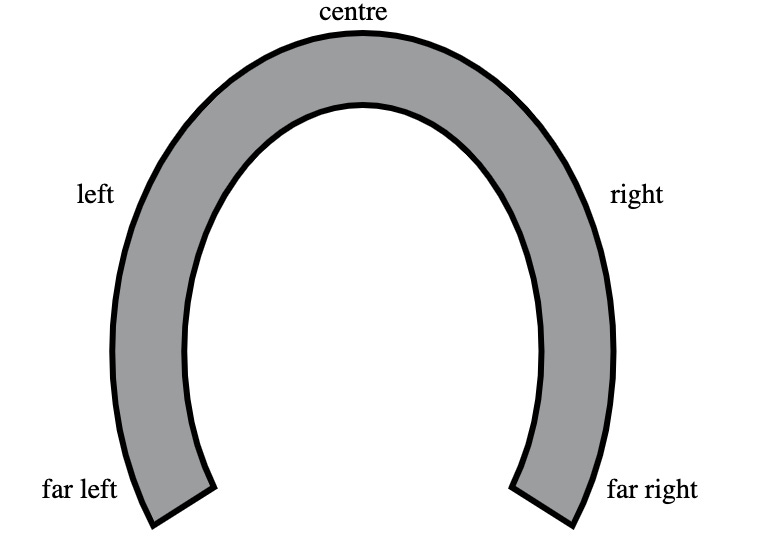

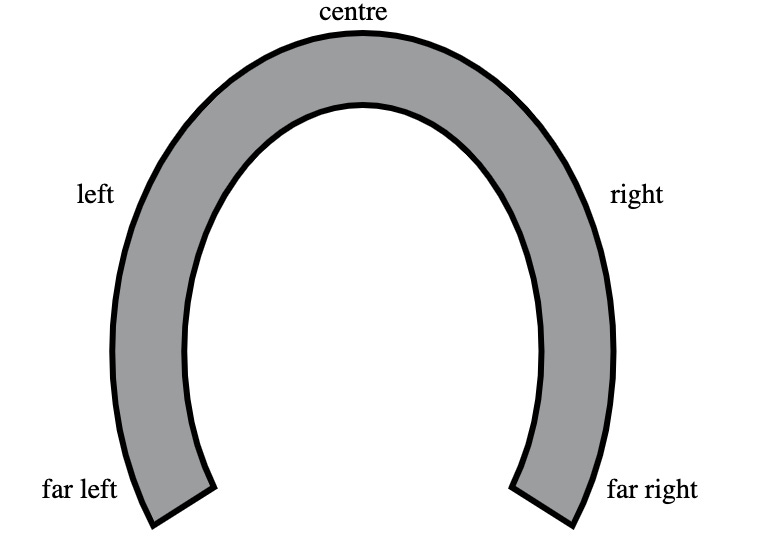

The horseshoe theory of ideology posits that the far-left and the far-right, rather than being at opposite and opposing ends of a linear political continuum, closely resemble one another, analogous to the way that the opposite ends of a horseshoe are close together.

Similarly, there is a sense in which capitalism and communism have converged. Consider the coronavirus: COVID-19 has obviously been bad for the economy and COVID-19 vaccines would obviously be good for the economy.[1] Econ 101 suggests that the solution would be for companies to turn a profit by making COVID-19 vaccines and selling them at a price exceeding costs.

The previous sentence obscures a great deal of complexity. Reasonable people can and do disagree on the ideal ways of funding, producing and distributing pharmaceutical products. A big part of the problem is making money through life-saving vaccines is a bad look.[2]

Fortunately, shareholder capitalism, coupled with the rise in passive investing, promises to save the day. In 2019, index funds that passively invest in stocks have exceeded active funds for the first time in the US.

As a result, there are basically a handful of institutional investment firms whose jobs are to hold onto a diversified portfolio of stocks that represent “the market”. (Here is an interesting side note on power law distributions in passive investing.) This portfolio of stocks includes huge, publicly traded pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer Inc.

If Pfizer is the first to market, there is a great asymmetry in the potential upsides to these passive funds as shareholders of Pfizer vs as shareholders of stocks representing “the market” generally. As Matt Levine writes:

BlackRock, for instance, owns about $16 billion of Pfizer stock. If Pfizer went to zero—if it bankrupted itself, selflessly producing and distributing vaccines—BlackRock (really its clients) would lose $16 billion. BlackRock owns about $2.9 trillion of other stocks; if a coronavirus vaccine allowed businesses to reopen and normal economic life to resume, and as a result those other stocks went up by 1 percent, that would more than make up for bankrupting Pfizer.

As such, government interventions to nationalize drug companies or impose price caps or suspend patent laws are unnecessary. Pfizer’s own large diversified shareholders are already incentivized to ensure COVID-19 vaccines are distributed in a way to ensure the economy experiences a broad recovery.

This is thematically resonant with my earlier essay on the distinction between value creation and value capture. Here, COVID-19 vaccines would obviously create far greater value than can be captured by pharmaceutical companies. (Indeed, the canonical way to bet on COVID-19 vaccines is not Pfizer’s stocks, but airline and cruise stocks.) Returning to Econ 101, these positive externalities imply that the merely self-interested Big Pharma will devote insufficient resources to such activities.[3]

However, thanks to the rise of passive investing, institutional investment firms like BlackRock are well-placed to “internalize the externality” and play a state-like role in solving this coordination problem. As Levine points out, such “externality internalization” has been manifested in other ways, such as BlackRock’s steps towards directing capital away from companies that “present a high sustainability-related risk”, motivated by climate change concerns.

Of course, the eagle-eyed reader will readily poke holes in this story.

For one, there is no evidence that large institutional investors like BlackRock have done anything remotely similar to bankrupting Pfizer to save the world, nor do they have reason to. The whole point of passive investing is to be, well, passive. Furthermore, in other contexts, the pursuit of these investors’ interests—whether via explicit coordination or implicit understanding—raises antitrust concerns: plausibly, if the major companies in a given industry are all owned by the Big Three index-fund companies, managers seeking to maximize value for their actual shareholders should collude rather than compete. (There is no clear evidence that this has happened.)

Another objection is that the world-saving company in question might not be within the warm embrace of passive index funds. As Levine himself noted, out of the drug companies contending to produce COVID-19 vaccines (as of July 2020, anyway), “Moderna has more concentrated owners than the bigger companies” and “[i]f you don’t like drug profits maybe you have to regulate them or nationalize them or whatever, that’s not my problem, that’s Congress’s problem.”

I’m sorry I lied. Capitalism is not communism, after all.